It is a fascinating time to be a psychiatrist. There is a flurry of new tools available to us which can help us deliver better care for suffering patients.

Psychotherapy has been around for over a hundred years. Various modalities, such as cognitive behaviour therapy and EMDR (eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing), amongst others, have gathered robust evidence in their efficacy in treating mental illness.

In the 1950s, fate smiled upon psychiatry. We discovered that a drug used to treat tuberculosis dramatically treated symptoms of depression. The era of understanding neurotransmitters and antidepressants was born. Antidepressants as a treatment have been amazing. They have saved lives and improved the quality of life for many.

Antidepressants work on the “monoamine hypothesis”. This hypothesis states that mood disorders such as depression and anxiety are due to depletions or imbalances of serotonin, noradrenalin, and dopamine. Over the last 70 years, antidepressants have refined into various classes to address the most symptoms with the most minor side effects.

For many people, this works like a charm. But, unfortunately, for some people, this strategy only partially works, and sometimes not at all.

Doctors do not like getting stuck. We like to help people feel better. But unfortunately, therapy and medication were all we had in our toolbox for many years, and it did not work for everyone.

The last few years have given us a new toolbox in “Interventional Psychiatry”. Whilst the research and science behind this modality are decades old, we are now beginning to understand how to pull it all together.

Interventional Psychiatry has two salient features separating it from previous modalities of treatment.

The one is that it has a unique delivery method. It is not an oral pill. Instead, it is an electrical or magnetic impulse, an intravenous or an inhaled treatment.

The second is that BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) gets released. BDNF encourages the growth of synapses in a process known as neuroplasticity. This process is essential because brain atrophy starts to occur if you have been depressed for long enough.

What is out there?

ECT (Electroconvulsive therapy)

ECT is an old treatment with a nasty rap. In the (bad) old days, severe seizures were induced and ECT got the reputation of being a last-ditch treatment that could cause memory problems and possibly even brain damage.

ECT has come far since those early days. Today it is a safe and effective treatment for severe depression. It is the gold standard for depression that has features of psychosis, active suicidality or catatonia. Using techniques such as ultra brief unilateral stimulation, means that side effects are minimal.

The biggest problem with it is that you need to go under anaesthetics for it. That means that it is an inpatient procedure, and a theatre and an anaesthetist needs to be booked for it.

TMS (Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation)

The brain is not just a chemical organ; it is also an electrical one.

And it’s beautiful.

What we now know about difficult to treat depression is that if two antidepressants don’t get someone feeling better, then the chances of improvement by adding more antidepressants or even switching out antidepressants get harder and harder. So, we as psychiatrists start getting a bit worried at this point. We start adding other medications like antipsychotics or mood stabilisers in the hope of winning and providing our patients with some symptom relief. This is known as “augmentation strategy”

As we add more and more drugs, we also add more and more side effects.

A very robust augmentation strategy is adding TMS. TMS uses a magnetic stimulus to create changes in particular areas of the brain. Areas like the DLPFC (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) which has been shown to be hypofunctioning in chronic depression.

TMS gives a “workout” to the DLPC- changing the polarity of the neurons, increasing blood flow, increasing glucose uptake and ultimately giving the area a kick start.

The absolute joy of TMS, besides its proven efficacy, is that it has minimal side effects. Unlike other augmentation strategies that can cause weight gain, hair loss, acne, sluggishness, TMS mostly causes a mild transient headache.

Ketamine

Ketamine is an old drug with a new application.

There is a lot of compelling evidence about its efficacy, particularly in rapidly reducing suicidality.

Ketamine can be given intravenously or as a nasal inhalation.

The intravenous method needs an anaesthetist. It can become tricky, especially if multiple doses are required.

The intranasal ketamine (Spravato by Janssen Pharmaceuticals) has all the benefits of quick relief from suicidality, with few side effects. In addition, it delivers directly to the limbic lobe (the emotional centre of the brain) and encourages neuroplasticity where it is needed most. It is a brilliant medication, but unfortunately, currently unaffordable to many with its eye-watering price tag.

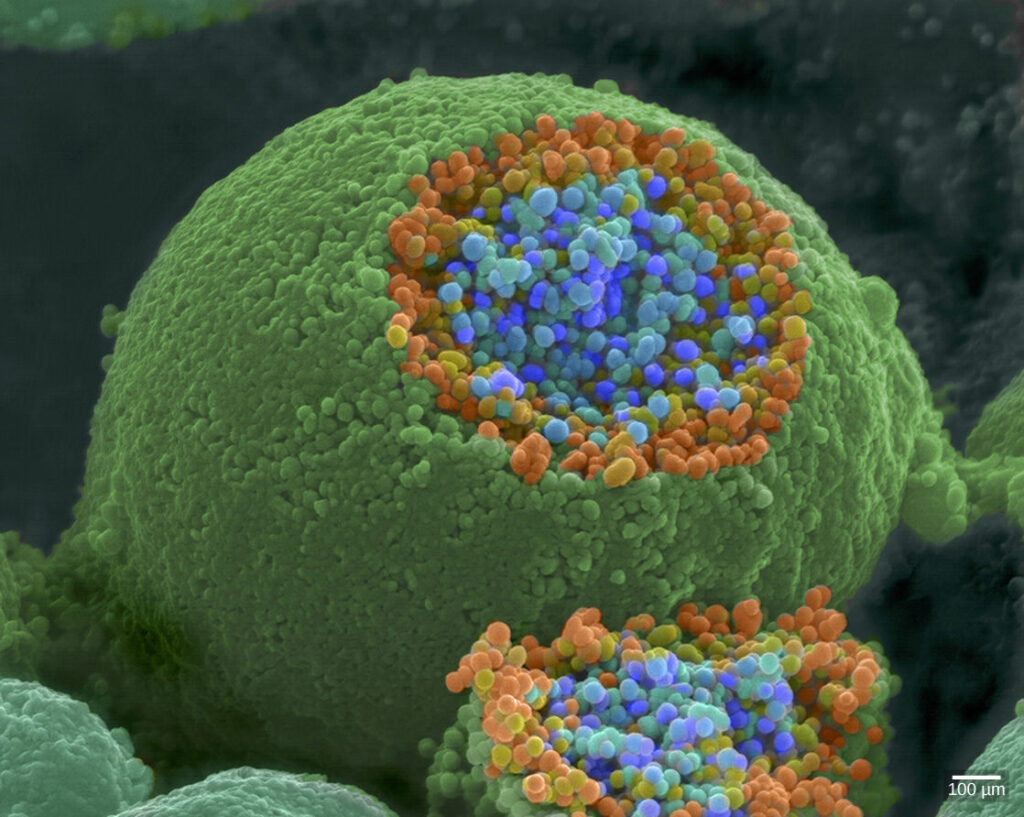

Psilocybin

Shamans have espoused the transformative effects of Psilocybin (magic mushrooms) for aeons. Traditional psychiatry considered it more the dangerous dalliances of the counterculture. However, more and more respected centres have been doing trials on Psilocybin and other psychedelics over the last decade.

Several studies have suggested that these drugs can be safely administered and can have positive effects on difficult to treat depression and PTSD.

Psilocybin is still illegal in South Africa, so your psychiatrist will not recommend it for you. However, we are carefully watching the evidence as it unfolds.